JUKE BOX JEALOUSY

“Happy Christmas to the prettiest girl in the Upper Third.”

Dawn Hutchens would never have written that if Mandy Carr hadn’t been forced to stay down a year. If Mandy hadn’t stayed down a year (and of course she had to, being unbelievably stupid and lazy), she’d have been in the Lower Fourth. And Dawn Hutchens would hardy have wished a happy Christmas to “the prettiest girl in the Lower Fourth.” For she, Dawn, was the prettiest girl in her year. Everyone knew that.

Well, that’s what everyone thought, at any rate. I, of course, knew better. It was one of my few consolations, you could say – my certainty that Dawn Hutchens wasn’t as attractive as she believed she was (her eyebrows were too thick and her teeth protruded, making a dent in her luscious lower lip whenever she smiled), along with my observation that – like Mandy - she found all subjects difficult, and French well nigh impossible. I was already particularly good at French, even in those days.

But I’m running ahead of myself. The events I’m telling you about took place half way through the previous spring term, when all three of us were in the Upper Third, and Juke Box Jury was at the height of its popularity.

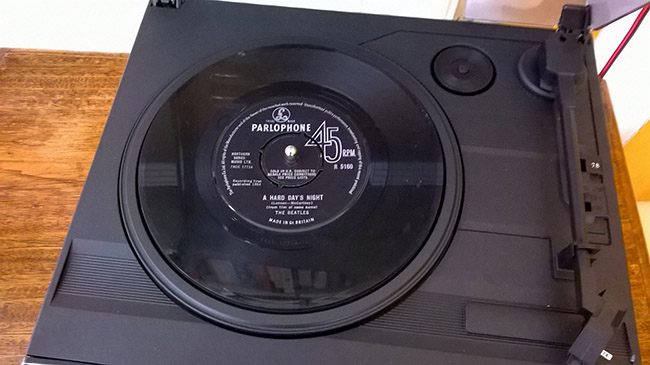

If you’re too young to remember Juke Box Jury, let me explain that it was a weekly television programme, chaired by one David Jacobs, in which a panel of experts (the word ‘celebrity’ didn’t yet exist) delivered their verdicts on the latest record releases. Each was accompanied by an appropriate sound effect – the optimistic tinkle of a bell for a hit, a guttural wail like water draining down a plug-hole denoting a miss.

It had been somebody’s bright idea to give the Upper Thirds – the babies of the institution, the tremulous eleven year olds – a chance to perform on stage before the rest of the school. And what better format than Juke Box Jury? A chairman (or, in our case, chairwoman), three panellists, and someone in charge of the record player. It would have mass appeal. Pop music, the TV association, those amusing little tinkles and wails. Our form teacher, Miss Ellison, experimented with a bell from a board game and a series of deflating balloons.

Mandy, needless to say, was one of the panellists. In the chair was Bridget Green, our form prefect. To my surprise, after Bridget had been democratically voted in by the class and Mandy had muscled her way forward as a panellist, Miss Ellison announced that she would be joined by Elspeth Raven and Jennifer Watts. That’s me. Otherwise known as Jenny. My friend Liz, in some kind of attempt at rhyming slang, used to call me Jammy Potts. I quite liked it at first, because I realised that it was proof of her affection and our intimacy. But, after Juke Box Jury, I tried to discourage the nickname. I noticed other people had started using it when they addressed me, and I decided that I disliked this kind of familiarity. We can’t allow our enemies to be familiar with us, now can we?

I could understand why our form teacher selected Elspeth as a panellist. Whereas Bridget, like every eleven-year-old class prefect, was merely a good egg, Elspeth was rather dazzling, a slightly exotic aura pulsing from her wavy, copper-coloured hair and her Scottish accent. She was a proficient musician, having passed with distinction I can’t remember which piano grade, shortly before being selected to sing the solo opening of ‘Once in Royal David’s City’ in the school carol concert. So Miss Ellison’s reasoning, though perhaps not absolutely fair on the other thirty or so damsels who had never been chosen to do anything, was entirely logical. A girl who knew something about music, whose speaking voice was pleasant on the ear and whose striking curls would undoubtedly give her a fabulous stage presence made an ideal rival to offer up just moments after Mandy had volunteered herself. I was sitting behind Mandy when Elspeth was thus catapulted to glory, so I couldn’t see her facial expression. But I noticed her lean over to Dawn and mutter something behind her hand. Her profile was dagger sharp. They both giggled, and Miss Ellison lobbed them one of her looks.

Then her eyes shifted to scanning the eager, brown-uniformed girls ranged in front of her, some of whom shot up their hands, and, as though suddenly seized by violent stomach spasms, moaned and squealed in a kind of ecstasy of painful longing.

“Jennifer Watts. I think we’ll have you.”

Am I imagining now, as I look back on the moment, that a barely-stifled gasp of surprise erupted with this announcement? Certainly Mandy Carr dropped the last remaining vestige of propriety as my name was intoned, spinning round in her seat to stare at me in a seething mix of astonishment and frank contempt.

I suppose Miss Ellison was simply trying to encourage me, to offer this quiet, retiring girl a little leg-up in the hierarchy of the Upper Third. For an instant, I realised this, and I was thankful. But the expression on Mandy’s face, and that swiftly-suppressed gasp from my classmates, served to undermine immediately any good my form mistress may have intended.

Afterwards, I discussed it with Liz, who chose (thank goodness) to relish the status conferred on her as Best Friend of selected panellist. I think she assumed that I would be coming to her for advice and training. Compared to me, indeed, she was very much at ease in the world of pop music and television programmes, and probably fancied herself also as rather more of a performer. But, being one of those souls who is inclined to see life’s positive side (and that, after all, is probably why – unconsciously – I chose her as my special friend), she seemed happy in her impending role of chief coach. We were in this together.

In the event, I neither wanted nor required Liz’s assistance. I knew I could do this one myself. Miss Ellison knew it too, which is another reason why she’d chosen me. It wasn’t just a matter of boosting my confidence. She wanted her class’s performance to be a success, after all. This could only mean that she trusted me to do well. And this trust was not misplaced. Of that I was certain.

It is a curious truth that sometimes the shyest people are those who come out happiest on stage. I suppose this is because they no longer have to be themselves. Who exactly I was going to be I had not yet decided. On balance, I fancied myself as Rita Tushingham. Yes, I could identify with that Bambi-eyed, vulnerable look. When I came to consider our chairwoman, mind you, I saw absolutely no points of contact at all between Bridget Green and David Jacobs. So evidently this was not the point of our entertainment. It was not a lookalike competition. All those foolish men cutting their fringe in a certain style and pretending to be The Beatles – that wasn’t for us. So if Bridget was not meant to be imitating David Jacobs, there was really no earthly reason why I should be Rita Tushingham, compelling as I found her.

A realisation dawned on me as I jabbed my feet, like one of the Ugly Sisters trying on the glass slipper, into my Featherlite shoes. Our gym teacher insisted these be worn by girls with veruccas. (Her disgustingly detailed inspections kept tabs on our status.) Having managed to squeeze in the toes of the second foot, I pulled on the back, wriggling my heel into place, and at that moment the whole thing came together in my mind. Miss Ellison had chosen me – not because she felt sorry for me; not because I reminded her of Rita Tushingham or Una Stubbs or Helen Shapiro… No, of course not: what a ridiculous idea. She had chosen me because she knew I would do it well. I’d get the character right. It was a matter of intelligence, and of language. It wasn’t actually a question of showing off. That’s why I’d do the job more successfully than Mandy. She would always be Mandy Carr, showing off. I wouldn’t be anything in particular. I’d just take the audience with me.

I stood up, and walked into the gym. About half the class was already in there. I took in the mats, the vaulting horse, the ropes and rope ladders, the wall bars.

There was one set of wall bars left. I didn’t wait for Miss Payne to issue instructions. I just started to climb. When I reached the top, I hung there, dangling my legs, kicking against the bars a little with my Featherlites, listening to the pre-lesson chatter bouncing off the walls, and feeling myself smile – up there, where no-one was watching.

*

We were back in the gym, but this time the elect were raised up, seated on stage for our dress rehearsal. There were very few of us. Looking back on it now, I don’t think it was the best of choices, this particular show. Not enough parts, you could say. Liz was in the corner, in charge of putting singles onto the gramophone – or record player, as we were calling it by then. But the equipment had to look right – otherwise the whole event would have lacked authenticity: a simple box with a lid. No speakers; poor sound quality as a result. But a juke box, more or less. Bridget Green, sporting a navy blue trouser suit (no doubt a concession to the spirit of David Jacobs) and some kind of dazzling orange cravat, sat on a chair centre stage; Elspeth and I sat on her right; to her left, resplendent in isolation and in a suede mini skirt, suede fringed waistcoat and green suede boots, Mandy Carr simpered, caressing her hair. From time to time, she glanced sideways at Liz, the only other occupant of her side of the stage, as though checking up on her. The whole time her body was mobile, restless. I meanwhile sat very still. From Bridget and Elspeth, as we awaited the cue to begin, there was the occasional nervous wriggle. I was surprised by how much I was enjoying these minutes of anticipation. Even the outfit I had chosen – a mini skirt (not as short as Mandy’s, naturally) from Dorothy Perkins in a tiny floral print, wet look boots and a luminous lime roll-necked ribbed jumper – had become a source of confidence.

There were no special lighting effects. This was the lunch hour. I looked straight out at the audience who had turned up to watch this rehearsal – our classmates, and a hotch-potch of other pupils who may have been genuinely curious, but who more likely were trying to avoid the playground. And I have no recollection that I felt especially anxious. Even when, just before we started, Mamzelle came bustling in and seated herself at the end of a row, more or less straight opposite Liz, my over-riding sensation was one of equanimity, eagerness even, to begin.

It’s not surprising, really, that the entry of Mamzelle left me fearless. She was a small, stout, beady-eyed woman who hurled chalk at her pupils, and who was notorious for her antics with the window pole, which she would balance in a position hovering just above the head of someone struggling to pronounce the horribly impossible – ‘grenouille’, for example. The window pole would descend ever lower, like the executioner’s axe, until the word was eventually uttered more or less to Mamzelle’s satisfaction. But these were tales that I had, at this stage, merely picked up from older girls. Mamzelle didn’t teach the babies of the school. For all I knew, the stories were untrue. Indeed, as she sat there, arms crossed beneath her large bosom, in what looked like cheerful anticipation, I suspected that she might simply be a mythical monster, cooked up by the Lower Fifth to frighten the rest of us. I almost dared to imagine that Mamzelle might actually approve of me, should I ever find myself in her class. For I was good at her subject – a natural, you might say. My mother was planning an exchange for me in the summer holidays with the daughter of an old friend of hers who lived just outside Paris. No, for me Mamzelle held few terrors. And this despite how I planned to deliver my act.

“Quiet please, everyone!” With these words, Miss Ellison must have given Liz the necessary signal, for the needle made shuddering contact and the first record began to chirp. We had been instructed to show some sort of response, so respond we did. Well, I wasn’t supposed to be looking at my companions’ faces, so couldn’t be too sure about them. But, as the record happened to be the Monkees’ ‘I’m A Believer’ - in the charts at the time, and rather a favourite of mine, I sat there giving what I hoped looked like an approving beam, nodding my head from time to time and doing a bit of a twist along with the beat. “I couldn’t leave her if I triiiied…” Out of the corner of my eye, I could spot Elspeth gyrating rather too wildly. Some of the audience started to clap to the music.

Liz (as planned) lifted the needle before the end of the song – to a disappointed moan from the body of the hall. This had been, you could say, by way of a musical introduction. Breaking swiftly into the pause that followed, Bridget welcomed everybody to Juke Box Jury, then introduced herself and her team of panellists. We had after all decided to invent names for ourselves. Elspeth was calling herself Stephanie McQueen; Mandy had settled (rather unimaginatively, in my view) on Sandy Carr; I’d adopted a French persona. Jeanne Qu’est que C’est. That was me. Quite clever, I thought. Apart from my own name, I suppose I had my father in mind, for he was a great fan at the time of film actress Jeanne Moreau. She stars in his favourite film – Jules et Jim. I thought the French accent would make for an interesting performance. Of course I hadn’t reckoned on the presence of Mamzelle. But – well, if I could pull it off in front of her at the dress rehearsal, I ought to be confident of success in the real thing.

Bridget (aka Davina Jacobs) dealt a surprise hand by turning first to me and asking for my opinion. After delivering various compliments on the catchiness of the tune and (this word delivered in what I hoped sounded like a convincing French accent but emerging as though it contained a ‘u’ with an umlaut) the “oomph” of the rhythm (“reezum”), I declared ‘I’m A Believer’ a “eat”. I’d practised this at some length, and concluded that this rather surprising word had to be the curious outcome of ‘hit’ pronounced French style.

Evidently the audience shared my verdict, and there was general applause. Thus I felt emboldened to shift round in my chair. (It was exciting enough to be sitting in a chair normally placed against the wall during assembly and reserved for the genteel backsides of teachers.) In this way, I could take note as Elspeth, inexplicably modulating her much respected Scottish accent into what sounded like an unsuccessful upper-class drawl, declared the song to be “top hole, absolutely top hole.”

And so to Mandy. She, predictably, milked her moment for all it was worth. But she wasn’t very good. There was much taking in of breath, as though she was dragging furiously on an invisible cigarette, much waving of arms, and some ambiguity as to the origins of her persona. She started off in what was presumably intended as a cockney accent. (It should be noted here that it is, in my experience, a staple of schoolgirl drama that characterisation can be achieved only by the adoption of some kind of alien pronunciation – as testified by all three panellists on this occasion.) By the time her verdict had reached its almost breathless conclusion, Mandy had slipped back into the clipped Queen’s English with which it was her custom to pass judgment on all around her.

And it wasn’t only the accent that must have struck her audience as inconsistent. During the Monkees’ number Mandy had been most conspicuous in tapping her green suede boot – the one that dangled, suede skirt riding high, across her thigh – in time to the music. Casting a sidelong glance in her direction, I’d taken in the face – vain, inane, really quite plain. But now, perhaps because the other two panellists had pronounced favourably on the song, she took it upon herself to amaze the multitude and come out dramatically - and here her whole frame positively shuddered as her lungs worked overtime – with a “miss” verdict. Her tongue hissed against her teeth on the final consonant, and I almost wondered whether we’d suddenly all been shifted inside a Christmas pantomime.

But Mandy aka Sandy Carr was of course in a minority, so the cheerful little song was declared a hit, and Bridget pressed down on the bell to create an equally cheerful little ‘ping’.

Everyone – participants and audience alike – were settling into this and positively enjoying themselves. A few latecomers drifted in and sat down at the back in time for the second piece. After a panic-punching hiatus, during which I could hear Liz coaxing the needle onto the disc (as the songs were not being played in their entirety, she was unable to use the automatic drop-down facility on the turntable), the frenzied strumming of Jimi Hendrix leapt out into the hall.

Well, this was a very different proposition. I knew what I’d be saying about this one. I’d got it all worked out.

Bridget may have been getting a bit flustered. I’m sure she wasn’t meant to ask Mandy’s opinion last again in this second round, but she did – and although in one sense it didn’t matter, because after all this was only the dress rehearsal, in another sense it’s what made all the difference. It certainly made a difference to Mandy, and so, eventually, to me.

The chairwoman remembered to turn first to Stephanie McQueen, who was once again of the plummy opinion that the number was “top hole, simply top hole, a future number one, a definite hit…” I assumed Bridget would then seek Mandy/Sandy’s verdict, by way of continuing to vary the order of panellists. But to my consternation – and evidently to Mandy’s also, she addressed me next.

“So, Jan…” (Jan? I’m Jeanne. Jeanne. No wonder she didn’t even attempt the surname.) Bridget cocked her head to one side, but continued to look straight out at the audience, eyes – I suspected – on her best friend Clare Arnold who sat bang in the middle of the front row. “Jan, what do you think?”

I decided I’d keep my eyes on Clare, too. “Zees is rubbish.” I made sure of the ‘r’, and paused. “Zere is no melody; zere is seemply… ‘ow you say? Much racket.” (Another Frenchified ‘r’). I kept my eyes on Clare, but found myself tossing my head in what I hoped would appear to be a kind of pert Parisian put-down. “Ze reezum is… dégolasse. No my friends…” Another pause. It really hadn’t been difficult to work out the punch line. It was all too obvious, if you ask me. “Zis is defineetely a Mees. Vhat ve call in France…” Slow down; timing is all… “Mademoiselle.”

I heard a titter, as understanding dawned amongst the punters. Someone, somewhere clapped their hands. Clare looked back at me and smiled, then nodded slowly.

The laughter, and the isolated applause, had evidently discomfited Mandy, who forgot entirely about the cockney voice and launched straight into breathy mode once more, pulling her skirt up even higher, spending some minutes attending to her hair, which seemed suddenly to require an emergency curling procedure from her fingers, and then dismissing the song.

“This was rubbish. Total rubbish. I can’t believe we’re even listening to it.” And her hand flailed again.

There was a silence. Rules were rules, and the game had to be played according to them. Tentatively, Bridget Green/Davina Jacobs cleared her throat and asked,

“So Mandy… er, sorry, Sandy. Is it a hit or a miss?”

“A miss of course, you idiot.” Mandy’s moody snap was fortunately drowned out by the slow, farting deflation of a balloon, blown up backstage and now, invisibly, released of air.

There were a couple more songs. I can’t remember what they were, nor how the panellists judged them. But I do know that I felt quite giddy when I rose at the end and, to the applause of the lunch-time audience, picked up my chair and walked with it off the stage, stacking it with the others in a corner and then slipping into a small classroom which opened off the back of the hall/gym and operated as a kind of green room.

There were blinds in here, which had been drawn so that we could get changed in privacy. But we lingered in costume for a time, waiting for our form mistress to give us her thoughts on how the rehearsal had gone. Afternoon lessons were not what we felt like right now. The door was ajar, and I could hear Miss Ellison and Liz discussing some technical point about the record player. “Just a bit more pace, Elizabeth. That’s what it needs.” The bar of fluorescent light hummed above us; the blind tugged slightly as a breeze caught it through the open window; Bridget and Elspeth were sifting through the contents of a packet of balloons and squealing under their breath.

Mandy approached me. She moved sinuously between the desks, like a snake. Her smile was not so much a curving upwards of the lips as a flaring of the nostrils.

“Well done, Jammy Potts. That was… not bad.”

“Thank you.”

“I think it went OK, don’t you?”

Nodding my agreement, I found myself stepping backwards, pinned to a desk. And she, it seemed, was preparing to coil herself around me.

“Yes. You did well, you funny little thing.”

Her eyes were stone-hard, greedy. The blind flapped again. Was it this that made a shadow pass over her face?

“But Jammy…” She was right up against me now. I could smell the remains of Wrigley’s spearmint on her fangs. “What’s all this ‘Mademoiselle’ business? What’s the point? It doesn’t mean anything.”

I’d always known Mandy Carr to be stupid. That, after all, was why she was eventually to repeat the year. But even the limited powers of Mandy’s brain could surely understand that ‘Miss’ translates into French as ‘Mademoiselle’. I mean, I wouldn’t have expected her to be capable of appreciating the subtleties of a pun: such wit was beyond her comprehension. But a bit of basic French?

She was continuing now. “No, it really doesn’t work, does it?”

I wondered if she was standing on tiptoe, for she seemed suddenly much taller than me; I felt myself shrinking. Again, the nostrils flared.

“What about something like…” Here, I was treated to her speciality wave of the arm. “Like ‘op-la-do?’ Yes.” She was pleased with that one. “’’Op-la-do.’ Try it.”

I tried it. I enunciated the stupid, meaningless compound far better than she could ever hope to.

How was I to know that Mandy would be told, just a few months from now, that she’d have to stay down? How was I to know that she wouldn’t be moving up into the Lower Fourth in September with the rest of us, and that I would thus be spared whatever she had planned for me?

All I knew, in the moment when Mandy demanded that I substitute a bit of silly nonsense for a smart, witty pun, was that if I didn’t comply my life at school would be made miserable. To defy the pride of this influential monster just for the sake of a few minutes’ vain success… No, it wasn’t worth it. I sensed this immediately. You see, she didn’t find it difficult to beat me.

So, in the actual, single performance of Juke Box Jury, presented to most of the pupils and staff of the school on the following afternoon as a half-term treat, my ‘Miss’ was no longer ‘Mademoiselle’. It was ‘’Op-la-do.’ I was still the best of the three panellists; of that I am certain. The most convincing and sustained characterisation; the clearest voice; the most considered use of language. You see, I always was the cleverest. But somehow, it fell rather flat. I tried not to look anyone in the eye, keeping my gaze on the honours boards at the back of the hall. I’d make it onto them a few years later.

As the strains of Englebert Humperdinck’s ‘Release Me’ faded away, there was a burst of applause and shouts of “Encore!” As instructed by Miss Ellison, we took a bow, and left our chairs to be stacked by other, lesser classmates. The gramophone had behaved impeccably. As I made my way into the classroom at the back, I heard Liz snapping it shut. Then her hand was on my shoulder, as she gave it a friendly pat.

“Well done, Jammy. You were… magnifique!”

The classroom was empty. Half-pushing me into it, Liz closed the door behind us, and, hand once more on my shoulder, drew me to a halt with a sharp squeeze. Then she succeeded in more or less spinning me round to face her. Liz was my best friend, in those days; I trusted her, whatever she did.

Now her eyes – grey, clear, penetrating, looked straight into mine.

“Jenny? Why didn’t you say ‘Mademoiselle’ this time?”

I felt something begin to flutter in my guts, but I pushed it down. Nothing must matter. It really mustn’t matter.

Liz persisted. “It was so funny. And clever. You had Mamzelle in stitches at the dress rehearsal. Didn’t you realise?”

No. I honestly didn’t. I shook my head. No-one had told me.

“Didn’t you hear her clapping?”

“Well… I did hear one person clapping their hands, but…”

“That was her. And she was in hysterics.”

Of course, this was quite a coup. But it had, after all, been only the dress rehearsal. It was the real thing that mattered. I’d let myself down. Why hadn’t Liz mentioned it at the time?

“I didn’t know she was in hysterics.”

“Well, it you weren’t looking in her direction, I don’t suppose you’d have realised. It was that kind of silent laughter – you know, deep, heaving laughter – sobs, almost, or… like spasms. And she was rocking backwards and forwards, and … sort of rubbing her eyes.” Liz demonstrated this last detail.

“What? Every time?”

I’d done the ‘Mademoiselle’ bit three times in all, at the dress rehearsal.

“Yes, every time you said it.”

Liz had brought her face right close to mine. It was, you could say, like Mandy all over again – so powerful, so overwhelming. But it was kindly meant. That, I assured myself, was why she’d remain my friend. And, of course, right now I needed her.

I dropped my eyes. “Mandy said… Mandy said…”

There was no need for any more. Liz sniffed, snorted, and had just enough time to hiss “Jealous bitch!” before the subject of our discussion entered the room, arm in arm with Dawn Hutchens, head high and nostrils flaring.

I wouldn’t look at her. I vowed I would never again look Mandy Carr in the eye. All my life, I told myself, I’d try and avoid her type.

Inspired perhaps by the other girls’ ostentatious intimacy, Liz put her arm round me for an instant, whispered, “I wish you hadn’t let her talk you out of it!” and marched out of the classroom, passing the other two without turning her head. Yes, she was an ally – but she would not have been enough had Mandy and her entourage chosen to turn on me.

The afternoon dripped, like cold rain, about my ears. I wanted to be muffled, hidden, scooped clear.

Mandy simpered at me. I tried a weak smile in return. Still, my primary sensation was one of cold. There followed shortly a kind of thawing. But it was a rapid thaw that threatened to melt out of control. There would be floods. I swallowed hard, screwing my eyes tight shut, to stop the flood from rising and spilling over.

I remember thinking at that moment, as the fluorescent bulb above us throbbed chilly light into the room, that I longed to be adult. For then I would have the knowledge and the confidence to chisel out a perfect revenge.

“You remember the time the Upper Third put on a kind of Juke Box Jury? And that strange little kid? What was her name? There she is – up there on the honours board at the end. She did the most brilliant imitation of a nutty Frenchwoman. And you remember the funniest thing about it? Mamzelle just loved it. Strange – but she was in stitches that day. So was everyone. ‘Mamzelle’ being ‘Miss’, of course. We all got the joke eventually.”

It could have been my most triumphant moment. Instead, it had been kicked back at me as proof of my inadequacy. I felt the kick somewhere around the area of the rib-cage. Sometimes, I can feel it still.

*

I’m not certain that I ever entirely got over it; I know my revenge never came. But somehow, from what I could tell, watching from the sidelines (confined ever afterwards to the wings, you might say), it seems that life got the better of Mandy Carr. Yes, life defeated her in the end. She collapsed, limp, like one of Miss Ellison’s farting balloons. It was something she and I shared, in a way: disappointment. I’ve worked for many years now as a translator – mostly of legal documents for the music industry. Mandy is to be seen from time to time presenting B-division chat shows on obscure cable television channels. I’ve never watched these programmes, naturally. But Liz, whose offspring are as screen-addicted as everyone else in their generation, keeps me informed. There was some scandal recently. I couldn’t avoid that one: I happened to be in Smith’s and all of a sudden there was Mandy Carr, her image leering at me from the front of the Mirror. Still, even as middle age began to crack her foundations, her flesh demanded attention. I remembered her skin as neutral, a sort of dull beige that a friendlier person than I might have called olive toned. How strange, I thought to myself, as my eyes looked into hers for the first time in thirty years - how strange that, even in a newspaper photo, such stridency should leap out from the brazen spread of skin on neck and cleavage. What she flaunted was probably fake by now, I mused, deciding not to bother buying a copy. The headline told me enough: some seedy liaison with a minor music celebrity whose wife was now divorcing him. In music, perhaps, our worlds still converged.

Liz rang me that evening. “Didn’t you always know she was a bitch?” No need for her to mention Mandy’s name. She knew I’d cotton on. It surprised me, really, that Liz’s hostility appeared to have lasted as long as mine.

But I didn’t want to talk about it. I try to spend as little time as possible dwelling on bitter things. About three years ago, soon after I’d started translating a contract for Sony’s Paris office, it was suggested to me that I hand over the task to a junior colleague. The reason given was that she, being younger, would more readily understand the nature of the material – something concerning charges to be levied for musical downloads onto MP3. I resented it deeply. But I said yes.

You see, I haven’t changed. Life, in a way, has taught me nothing. Juke Box Jury prepared me for what it would be like. Mandy, it would appear, hasn’t changed either. And she hasn’t learned a thing. That, I understand, is the revenge that will have to satisfy me.